To say that I had high hopes for the 2025 Met Gala would be an understatement. As soon as this year’s theme was announced, and the book that inspired it was revealed, I started harbouring high expectations, albeit slightly jaded, given the not-so-pure intentions of Anna Wintour (although I am sure that she would have you believe otherwise).

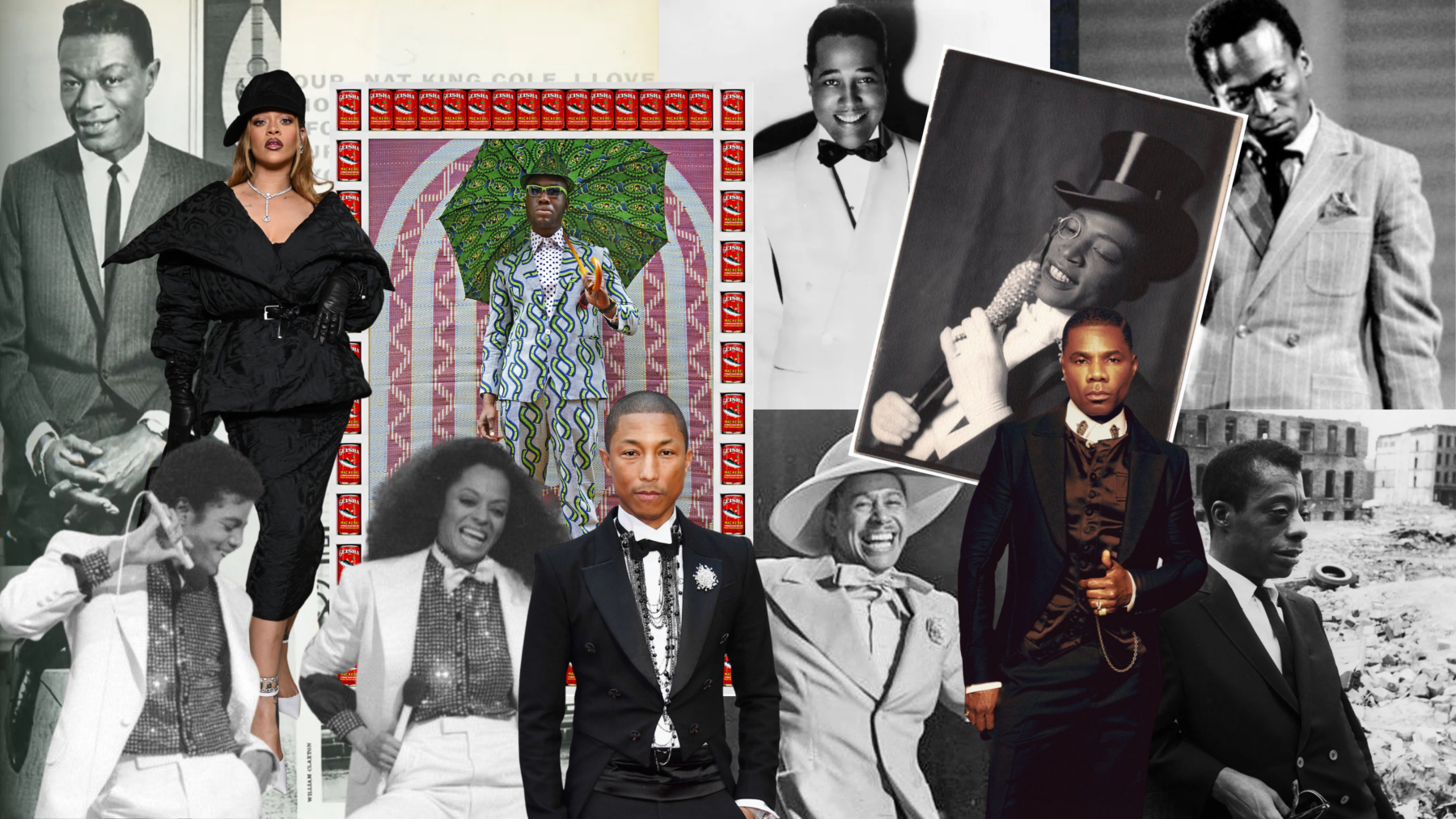

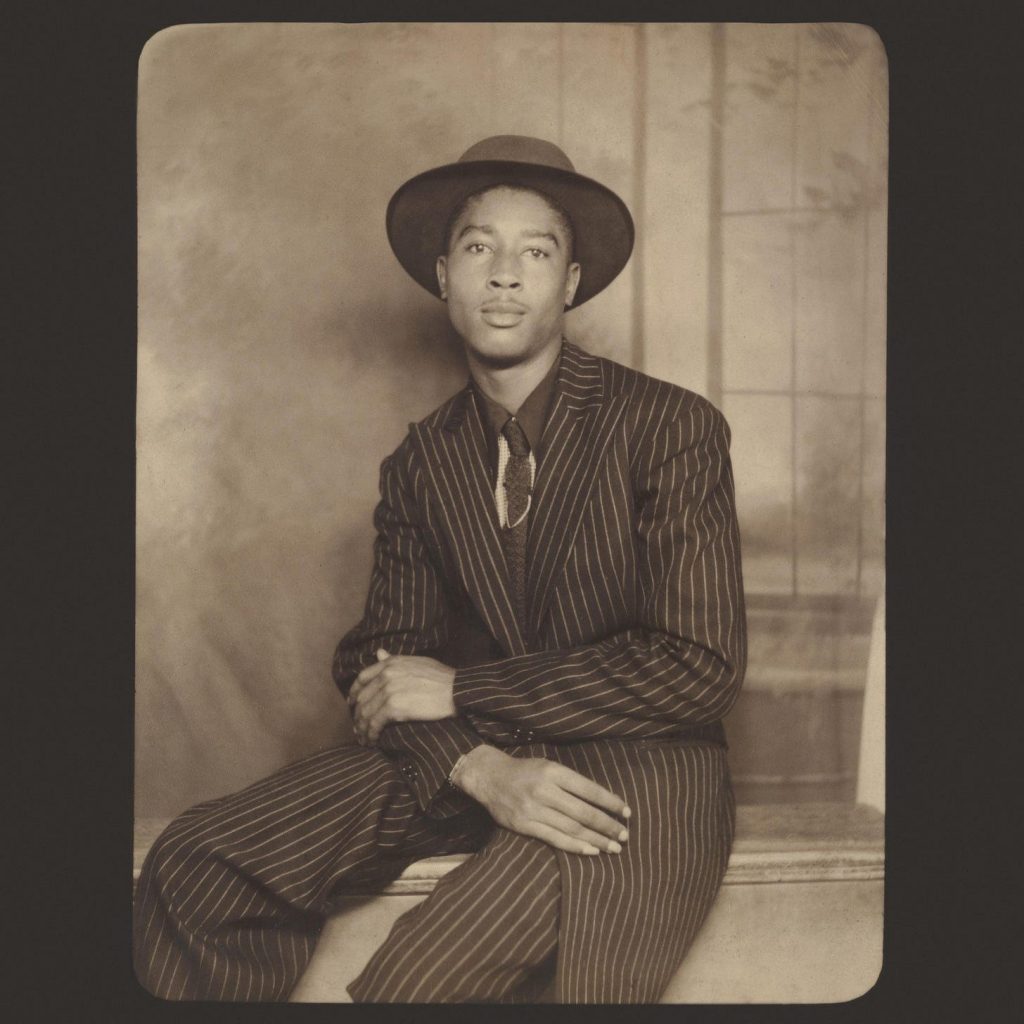

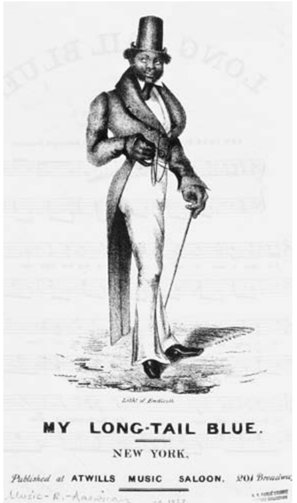

This year’s theme was “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” – a celebration of black dandyism, and the historical journey and it’s transformative significance since the onslaught of slavery. A dandy was typically used to infer a man who “devoted fastidious attention” to the way he dressed, and had strong connotations to masculinity and social class during the 18th and 19th centuries (Adams, 2023). Black dandyism was borne during the Atlantic slave trade period (The Met, 2025), and represented the use of fashion, style and charisma to both distinguish oneself from the absence of privileges, and act as a form of resistance to slavery, prejudice and racial injustices (The Met, 2025).

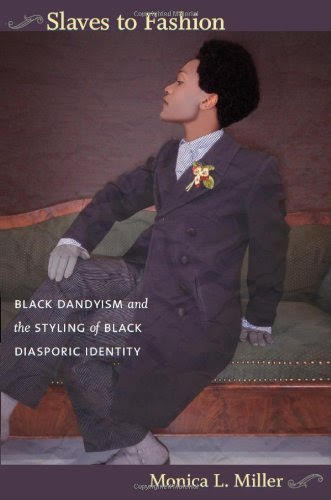

The book that the Gala is centred on: Slaves to Fashion – Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity written by Professor Monica L. Miller, is visceral in its ability to demonstrate the trials and tribulations that African Americans have undergone to resignify fashion, and more broadly, how black dandyism became “a strategy of survival and transcendence” (Miller, 2010, pg 9). This year’s theme was particularly poignant for it was an opportunity to showcase how centuries of trauma, oppression and thievery of self-identity have been reclaimed, repurposed, and converted “into presence through self-display” (Miller, 2010, pg 10). This was to be a momentous occasion, made especially so, given the divisive times that we are so heavily entrenched in. So please, bare with me, as I divulge to you my disappointments which have been trifold.

* Many seem to not have made any efforts to understand the theme itself, instead often clad in non-sensical or poorly justified/explained outfits.

* The lack of black designers at the Gala.

* This one is more personal, and perhaps a contentious take. However, I was disappointed at the lack of solidarity, knowledge and acknowledgment that South Asian celebrities displayed for a theme centred on BLACK DANDYISM.

Let us begin this dissection.

Convenience Cosplay

It was hard for me to digest the sheer lack of adherence, let alone acknowledgement of the theme. I understand that the dress code specific to attendees was “Tailored for You,” i.e., incorporate your own personal style, tailoring and silhouettes. However, what over-arching theme does the dress code stem from, and how can that be so easily overlooked? How would you, as an attendee, not want to educate yourself on a topic so profound and integral to America’s bloodied history? It reeks of tokenised effort to me.

The likes of Hailey Bieber, Kylie and Kendall Jenner, Joe Burrow, Rachel Brosnahan, Shakira, Sadie Sink, Anne Hathaway…all really missed the mark, and sadly I can keep the list going. Most of them wore what they would to any normal gala, or perhaps even to a 9-5 corporate job – it was a blatant disregard and denouncement of the theme in my eyes. But let’s specifically touch on a few that felt very much like a slap in the face. Sydney Sweeney’s custom Miu Miu dress, was said to have been inspired by Kim Novak, a white-American actress and painter. Miss girl, did you see what the theme was about? Blackpink’s Lisa, was an affront to the eyes, in her LV designed underwear that seemed to have Rosa Parks etched across her nether regions. The indignity of it all. Amelia Gray really took the theme as an opportunity to insult and appropriate black culture and history by sporting a durag with what can only be classified as lingerie. Don’t piss me off. Sabrina Carpenter in her LV leotard-tuxedo abomination also teed me off, and can people please wear some pants, how is this in line with the theme?

It seemed like there was an amalgamation of insensitivity, wilful ignorance, haphazard participation, and a lack of general education on the gravitas that black dandyism heralds. I say all this to say that education is imperative for change to occur, and performance without education and intentionality is a missed opportunity, ie, did anyone read Miller’s book???. We need people of other races to champion, and vigorously participate in these sorts of events. Afterall, burdens are best alleviated when they are shared.

In many ways this was a test, and a lot can be construed from this action (or inaction I should say) alone.

Really understanding, and “holding space” (no Wicked pun intended) for the theme, should have looked like a “reimagining of the past”, and “grounded in irony, satire and wit” (Miller, 2010, pg 15). Given that black dandyism subverts from and reshapes traditional notions of race, class, gender and sexuality – I would have liked to see this captured in the physical. Miller’s references to a “glittering uniform” (Miller, 2010, pg 30), “two-piece silk suit, pants of knee breeches and a short and collared jacket…Burnt cork, white stockings,… a white hat…” (Miller, 2010, pg 37), to “monocle, cambric handkerchiefs, cologne water…” (Miller, 2010, pg 111), could have been a great place to seek both historical understanding and creative direction. The gala should have been performative and exaggerative, for that is what black dandyism relays – an abstraction of reality.

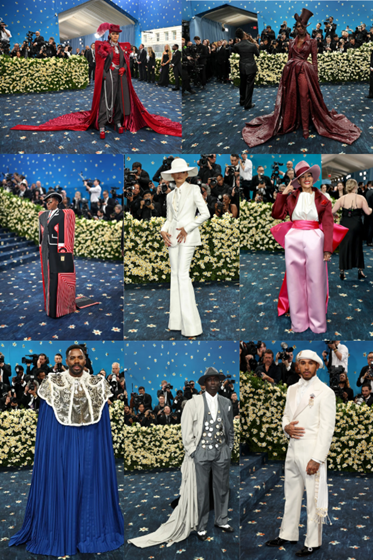

Thank you to the below for capturing that so beautifully.

Teyana Taylor, Lewis Hamilton, Zendaya, Rihanna, Jodie Turner Smith, Tracee Ellis Ross, Tessa Thompson, Janelle Monae, Laura Harrier, Lupita Nyong’o, Imaan Hammam, Lauryn Hill, Sarah Snook, Hunter Schafer, Shaboozey, Whoopi Goldberg, Khaby Lame, Andre 3000, Colman Domingo (the cape as an ode to Andre Leon Talley was lovely) etc.

Where Art Thou, Black Designers?

I will keep this one brief, but the lack of black designers worn by prominent celebrities was shocking. This would seem to me the most logical approach – seeking the help, vision and historical knowledge of talented black designers. Giving them a platform and much needed exposure in an industry that is accustomed to overlooking Black talent. Did we learn nothing from Mr Talley?

It was disappointing to see prominent celebrities, who although hit the mark regarding the theme, did so with non-Black designers. Tyla even wore British-Nigerian designer Tolu Coker days preceding the event, but opted for a Jacquemus dress on the day of. And might I say, the former was far more captivating.

The Mississippi Masala of it all

Let’s not mince words here. There has always been a complex relationship between Indians and racism towards black people. Colourism pre-dates British occupation, and has intensified and extended beyond the time of the Raj. The racial tensions and complexities that exist between the two communities is also captured succinctly in Mira Nair’s movie Mississippi Masala, and that is what first came to mind when I saw the varying opinions regarding what South Asian celebs wore to the gala.

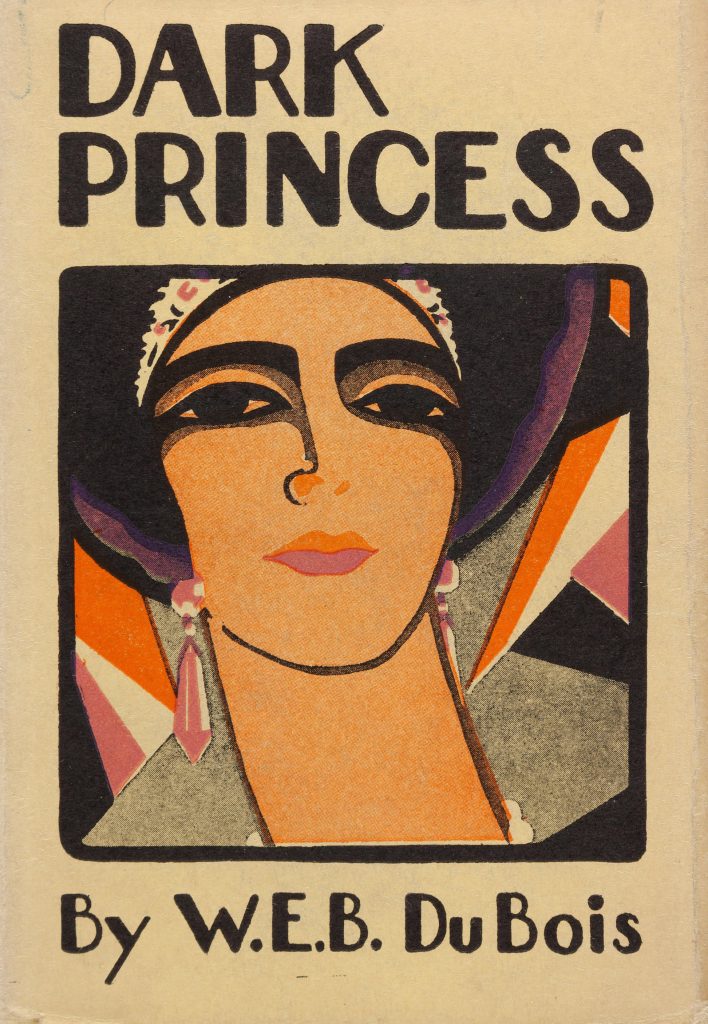

I personally expected solidarity in ideas between black and South Asian designers (when designing for South Asian celebs), an exchange of thoughts and shared empathy for a colonial past that shadows both. Miller explores this inter-racial solidarity in Du Bois’ book Dark Princess, where Madhu, a biracial and bicultural offspring of an African American and South Asian Indian, “defies racial categories – he embodies a deconstruction of racial barriers as well as solidarity among darker races” (Miller, 2010, pg 167). Instead, there was a separation that seemed to exist between the Indian attendees and the African Americans, with the former using the gala as a purely personal ode, rather than as an opportunity to educate oneself on the theme. I found Shah Rukh Khan’s explanation of what the theme meant to him to be poor, and self-involved. A better effort could have been made to incorporate black dandyism, not to mention the look itself was BORING.

However, I do see both sides. Indians championing Indian heritage and artistry, for when are we ever really given the stage to do so? We cannot turn a blind eye to the West’s growing hostility and propaganda against South Asians, even as it cherry-picks elements of our culture for colonial and capitalist gain. Furthermore, dandyism is inherent to our culture and also acts as a subversion to colonialism. Diljit Dosanjh’s custom Sikh royal ensemble designed by Prabal Gurung, is especially poignant given the marginalisation of Punjabi Sikhs in India by alt-right Hindus since the partition in 1947.

Yet, my gripe lies in the timing. Why now? Can’t black people have a platform, championing them, entirely for themselves, for once? A better way to go about this would have been a combination of both – a nod to Indian heritage, while advocating the theme of black dandyism. Bad Bunny did this very well with the integration of his own culture with that of black dandyism. In terms of South Asians, Mona Patel, Natasha Poonawalla, and Mindy Kaling were fantastic examples of also bodying the theme.

All this to say, we are tired, do better, be better.

References

Adams, J.E. (2023) The Dandy, Oxford Bibliographies.

Miller, M.L. (2010) Slaves to fashion: Black Dandyism and the styling of black diasporic identity. Durham: Duke University Press.

The Met (2025) Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.